Cases by DT Ioulianos Moustakis and MDT Andreas Chatzimpatzakis

Producing dental restorations that are not recognizable as such – this is probably the ultimate goal of every dental technician. For a long time, pursuing this goal was complicated by core materials whose optical properties were very different from those of natural teeth. The dark metal or opaque zirconia substructures had to be masked by applying multiple layers of intensively coloured ceramic powders, topped by more translucent porcelains imitating the enamel.

The rise of modern, tooth-coloured core materials such as lithium disilicate and zirconia has changed the game. With a core that is highly aesthetic, translucent and close to the final shade, it became much easier to produce a restoration that is virtually indistinguishable from the adjacent teeth. The thickness of the porcelain layer decreased as did the number of shades to be combined and necessary bakes to be conducted. The use of the existing porcelain systems for the new micro-layering techniques posed several new challenges: those systems originally developed for opaque zirconia were indicated for the more translucent zirconia core materials, but usually not for lithium disilicate. Moreover, the complexity of the systems made their use unnecessarily complicated for inexperienced users.

Consequently, Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc. developed a new porcelain system for micro layering on zirconia and lithium disilicate core materials. The portfolio of CERABIEN™ MiLai, which refers to micro-layering and the Japanese word for future (mirai), consists of 15 internal stains (13 tooth colours including Bright to boost the translucent and Fluoro to boost the fluorescent effect, and two tissue colours) and 16 porcelains (12 tooth porcelains and four tissue porcelains). Hence, it enables dental technicians to implement a modernized version of the original Internal Live Stain Technique developed by Hitoshi Aoshima in the early 1990s in a porcelain layer of minimal thickness.

The following demo cases are used to show how to achieve lifelike aesthetic restorations based on aesthetic zirconia and on lithium disilicate. Illustrating each step, the cases allow users to anticipate how much time and effort can be saved compared to traditional layering techniques.

CASE 1

MAXIMALLY SIMPLE APPROACH ON LITHIUM DISILICATE

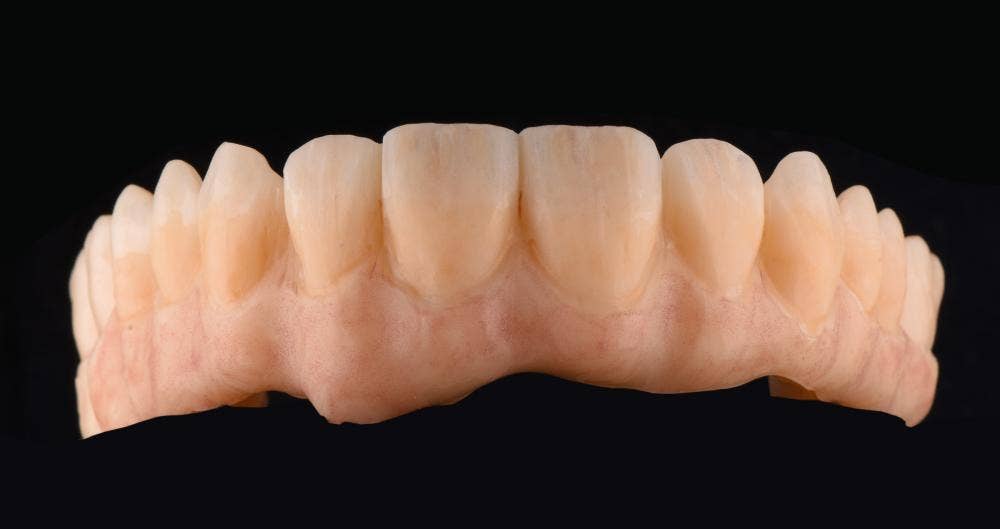

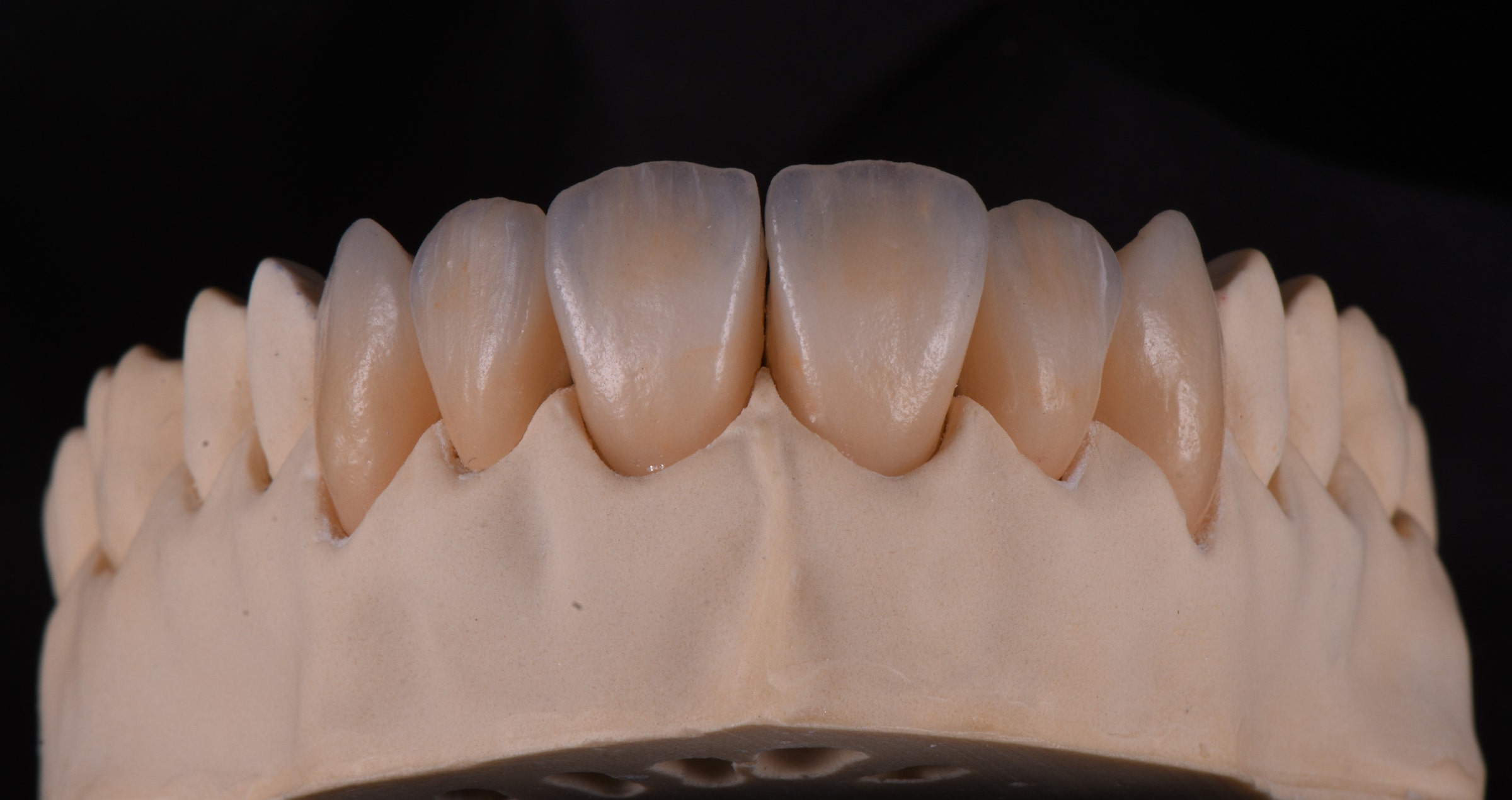

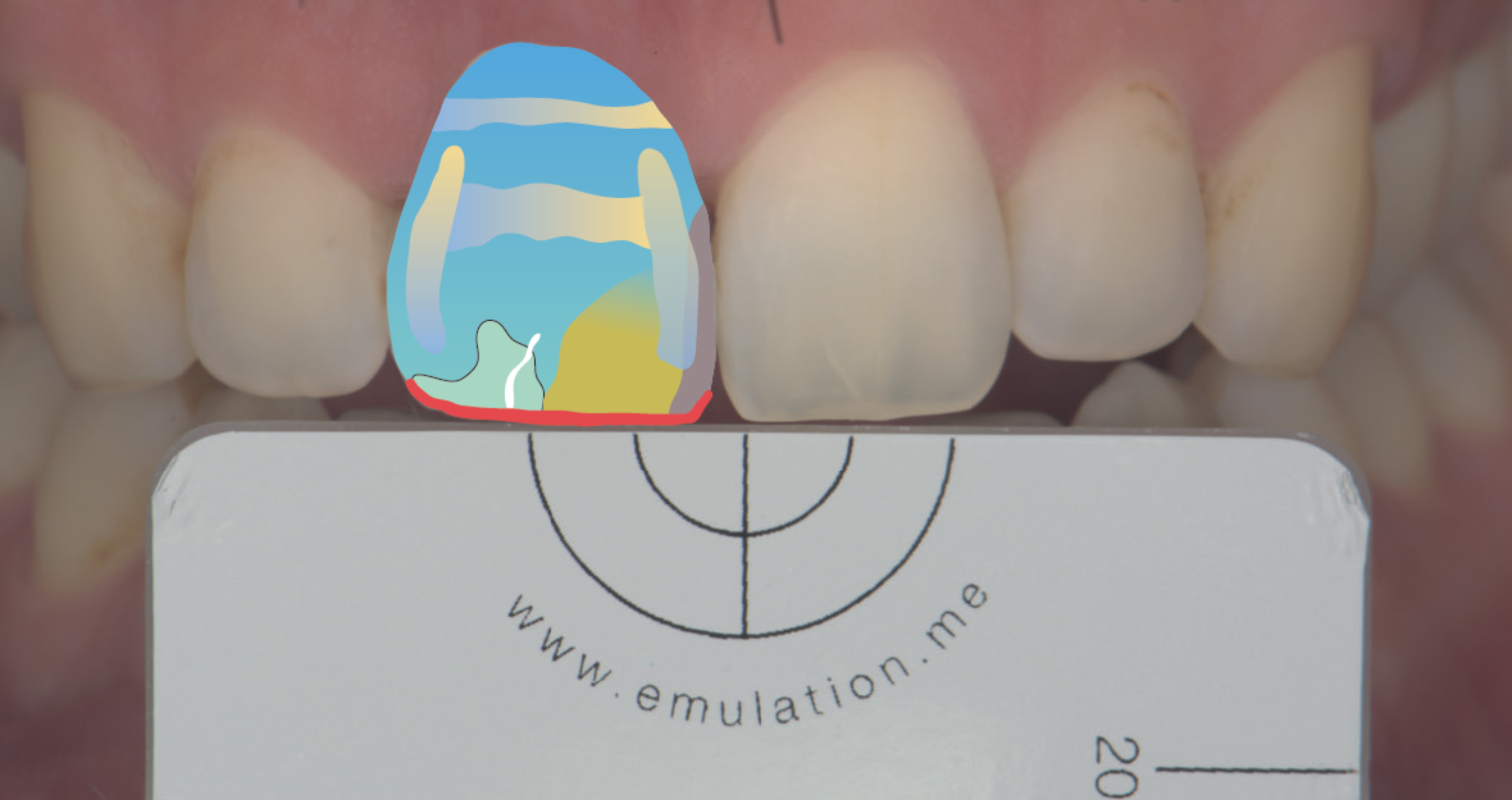

In this case, the idea was to restore the six maxillary anterior teeth in a simple way. The selected core material for the planned veneers was Amber Press (HASS Bio) LT in the shade B1. The lithium disilicate restorations were pressed with a micro cut-back and their fit was checked on the model, followed by surface texturing, sandblasting and steam cleaning [Fig. 1a]. When the veneers are milled instead of pressed, the procedure is the same. After that, the restorations are ready for the application of the CERABIEN™ MiLai internal stains for characterization of the core. In order to achieve the desired result, it is critical to mix the selected stains with the internal stain Bright responsible for a translucent effect. The chroma map for internal staining is shown in figure 1b, the outcome of the procedure in figure 1c. Subsequently, the veneers were built up to their final anatomy with selected CERABIEN™ MiLai Porcelains [Fig. 1d] to imitate the enamel and create a window effect. In this approach, simple layering and a single bake are sufficient to create the desired restoration. After glazing with Clear Glaze, finishing of the restorations was accomplished with paper-abrasive cones, a rubber polisher and polishing paste. The outcome is shown in figure 1e.

Fig. 1a. Pressed lithium disilicate veneers after surface optimization (grinding), sandblasting and steam cleaning on the model.

Fig. 1b. Chroma map for the application of CERABIEN™ MiLai Internal Stains to the lithium disilicate surface. We selected B+ (red colour) for the cervical area. For the proximal and middle incisal areas, Incisal Blue 1 & 2 (gradient blue colour) were applied and incisally in the middle, we chose Cervical 2 (orange colour). Tip: all internal stains were mixed with Bright and IS Liquid.

Fig. 1c. Appearance of the veneers after the application of CERABIEN™ MiLai Internal Stains.

Fig. 1d. CERABIEN™ MiLai Porcelains applied on top of the internal stains: LT1 is used for the cervical area (red) and a mixture of TX and E2 (30:70 ratio) for the middle and the incisal third.

Fig. 1e. The final restorations after glazing with Clear Glaze and mechanical polishing using paper-abrasive cones, a rubber polisher and Pearl Surface Z (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc.).

Images courtesy of Andreas Chatzimpatzakis.

CASE 2

ADVANCED APPROACH ON LITHIUM DISILICATE

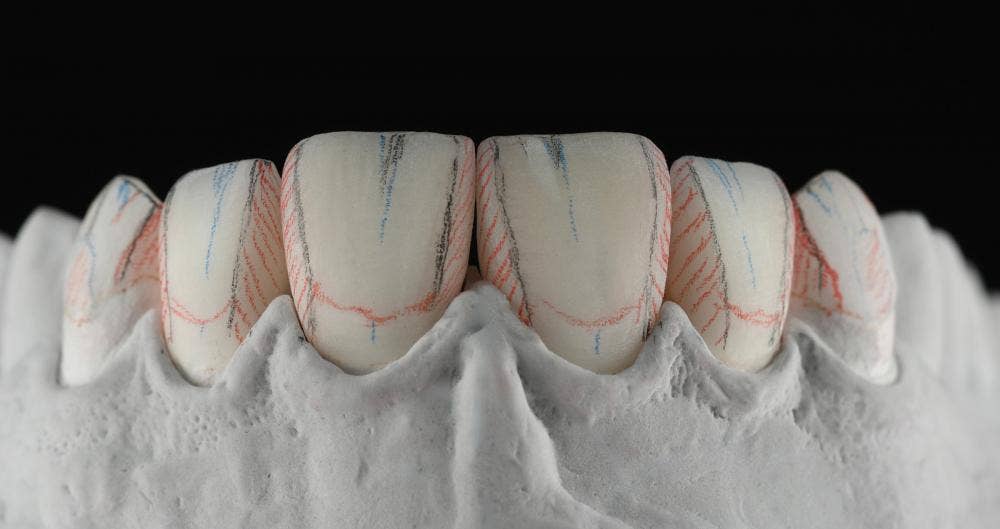

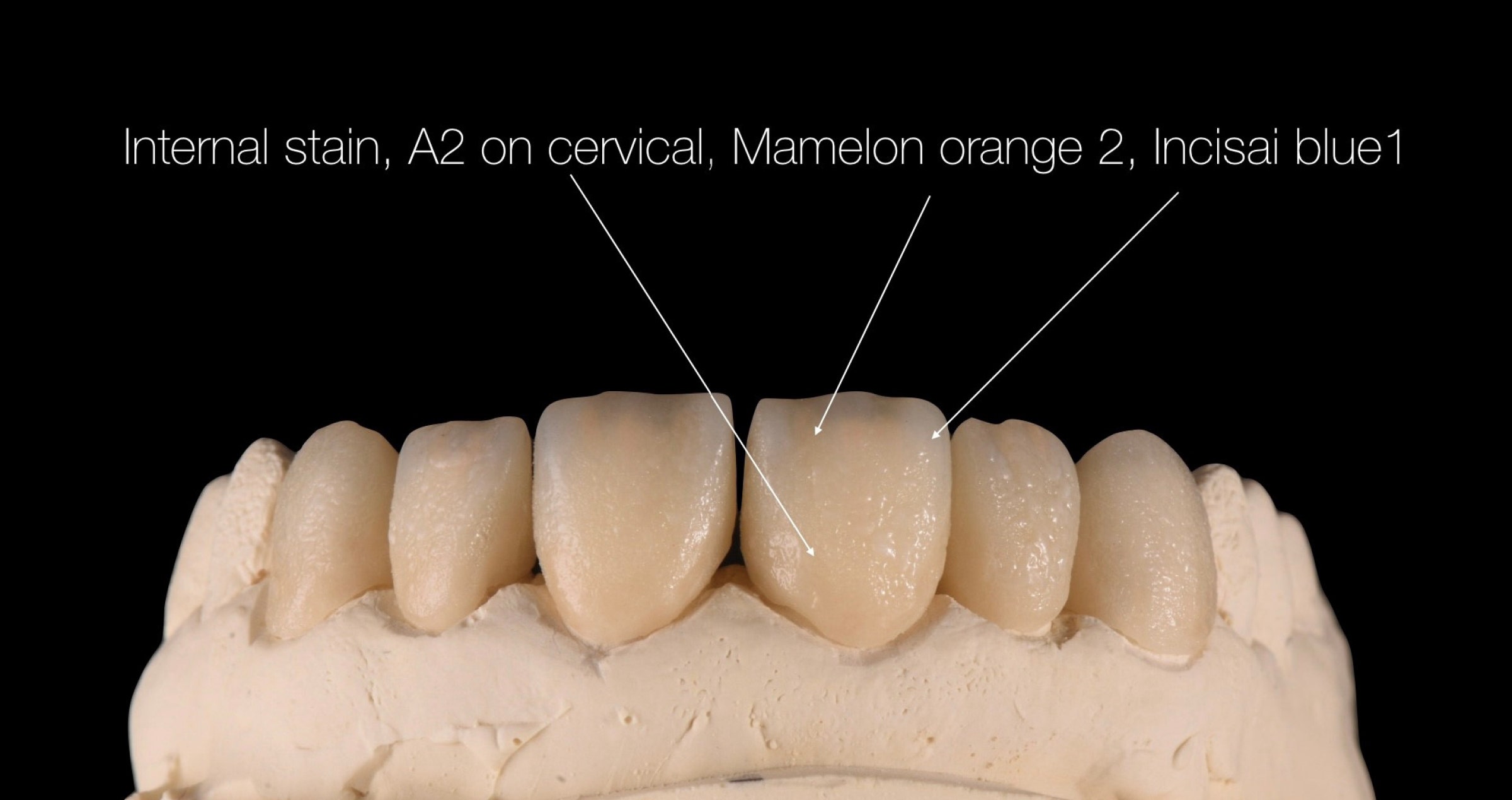

In order to imitate a more complex inner colour structure with mamelons, different levels of translucency and more individual effects, a slightly more complex micro-layering approach was selected. Again, the core was produced using Amber Press in the LT variant and the shade B1. After pressing and fitting on the model, we reduced the incisal third to create space for the transparent porcelain [Fig. 2a]. Subsequently, an extremely thin layer of CERABIEN™ MiLai Porcelain adding translucency to the enamel surface (TX) was applied in the incisal third of the veneers [Fig. 2b]. In this way, it is possible to create an optimally translucent basis for the application of the internal stains. The first bake was conducted and the surfaces were sandblasted as well as steam cleaned to create the conditions needed for internal staining [Figs. 2c and 2d]. The chroma map for and outcome of the internal stain application are shown in figures 2e and 2f. Afterwards, a final layer of CERABIEN™ MiLai Porcelain was applied [Fig. 2g]. All four incisors received a layer of LTx to add ultimate translucency and opalescence to the enamel, while LT1 was the material of choice in the cervical third of the canines, where LTx completed the layer in the other areas. As LT1 is slightly less translucent and opalescent, a natural effect is obtained in this way. The outcome obtained after glazing and mechanical polishing is shown in Figure 2h.

Fig. 2a. Lithium disilicate veneers reduced for the advanced layering procedure involving more porcelains and bakes.

Fig. 2b. Thin layer of TX applied to the incisal third of the restorations to boost the translucency in this area.

Fig. 2c. Appearance of the veneers after the first bake.

Fig. 2d. Ceramic surfaces after sandblasting and steam cleaning.

Fig. 2e. Chroma map for the application of the internal stains. Cervical 2 was used for the cervical third, Incisal Blue 2 for the proximal regions and Mamelon Orange 2 for the mamelons. As mentioned before, the selected internal stains were mixed with Bright.

Fig. 2f. Appearance of the veneers after the bake of the applied CERABIEN™ MiLai Internal Stains.

Fig. 2g. Final build-up to reach the desired shape of the veneers. LTx is the only material applied to the central and lateral incisors, while the canines are built up with LTx in the incisal and middle and LT1 in the cervical third.

Fig. 2h. Glazed and polished veneers on the model.

Images courtesy of Andreas Chatzimpatzakis.

CASE 3

ADVANCED APPROACH WITH GUM AREAS ON ZIRCONIA

In this case, a highly complex ten-unit bridge with gum parts in the anterior region had to be produced. The selected framework material was KATANA™ Zirconia HTML Plus (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc.), which offers a multi-layered colour structure, an optimized translucency and the high flexural strength required for long-span bridges. The restoration was milled in an anatomically reduced design and the surface texture was optimized with rotating instruments before sintering [Fig. 3a]. After the final sintering procedure, the restoration had a favourably high translucency in the incisal region and a natural shade structure [Figs. 3b and 3c]. In the first step of the micro-layering procedure, the application of the CERABIEN™ MiLai Internal Stains was planned and carried out [Figs. 3d and 3e]. Subsequently, different layers of CERABIEN™ MiLai Porcelain were applied. The images 3f to 3h reveal which shades were combined and illustrate the procedure, while the outcome before and after the last bake is shown in Figures 3i to 3k. In the next step, the gum areas were completed using the CERABIEN™ MiLai tissue porcelains Tissue 4, 5 and 6 in the order and locations described in Figures 3l to 3o. In the final layer, Tissue 1 was mixed with ELT1 to imitate the labial frenulum and with LTx to create a smooth transition to the natural gingiva [Figs. 3p and 3q]. The final restoration is shown in Figure 3r.

Fig. 3a. Milled restoration after surface texturing.

Fig. 3b. Shade and translucency of the sintered zirconia restoration.

Fig. 3c. Highly translucent bridge on the model.

Fig. 3d. Chroma map for the application of CERABIEN™ MiLai Internal Stains.

Fig. 3e. Applying a mixture of Bright, Salmon Pink and Tissue Pink to the gum area.

Fig. 3f. Application of CERABIEN™ MiLai E2 to add translucency to the structure.

Fig. 3g. Application of Tx and a mixture of Tx and CCV-2 to individualize the cervical and incisal areas while boosting the translucency of the enamel in the middle and incisal third.

Fig. 3h. Adding a final layer of LT1 for additional translucency and opalescence.

Fig. 3i. Appearance of the ten-unit bridge before the bake – labial view.

Fig. 3j. Appearance of the ten-unit bridge before the bake – palatal view.

Fig. 3k. Appearance of the ten-unit bridge after the bake.

Fig. 3l. Application of small amounts of Tissue 5 …

Fig. 3m. … covered with a layer of Tissue 6 alternating with Tissue 5.

Fig. 3n. Following another bake, Tissue 5 is applied in the proximal areas.

Fig. 3o. How to combine Tissue 6 and Tissue 4 in the next layer.

Fig. 3p. How to complete the tissue layer with Tissue 1, locally mixed with ELT1 or LTx.

Fig. 3q. Restoration before the final bake.

Fig. 3r. Final ten-unit bridge ready for placement.

Images courtesy of Ioulianos Moustakis.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

DT IOULIANOS MOUSTAKIS

Germany

Dental Technician/Photographer

1985 - 1987 Studied at the School of Dental Technology (SBIE) in Athens / Greece

1997 - 1998 Master school in Berlin

2007 - Education as Maxillofacial prosthetic technician (IASPE)

2010 - Advanced education in Functional diagnosis temporomandibular joint

2011 - 2012 Curriculum implant prosthetics for dental technicians (DGZI)

2013 - 2014 Education as a graphic designer at the Media Design Hochschule (MDH) in Berlin

2015 - 2017 Education as a photographer at the Photocentrum of the Gilberto Bosques VHS Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg

2014 - 2016 - 2018 Further training at Noritake/Kuraray in Japan

2019 - International Instructor Noritake/Kuraray

2019 - Certified trainer of Teeth Morphology carving (Osaka Ceramic Training Center)

1998 - Implant Dental Studio - Athens/Greece

2010 - Zirkler & Moustakis Dental Technology - Falkensee/Germany

2020 - Giuliano Dentaldesign - Falkensee/Germany

Publications in Dental Journals

2014 - 5/2014 Dental Dialogue/Germany

2015 - 10/2015 The International Journal of Dental Technology/Japan

2018 - 1/2018 Cosmetic Dentistry/Germany

2018 - 4/2018 Zahntechnik Zeitung/Germany

2018 - 5/2018 Das Dental Labor/Germany

2018 - 5/2018 Dental Dialogue/Italy

2018 - 10/2018 Laborama/Greece

2019 - 1/2019 LabLine/Hungary

2019 - 3-4/2019 Dental Technologies/UK

2020 - 4/2020 LabLine/Hungary

2021 - 1+2 LabLine/Hungary

2021 - 5/2021 + 12/2021 Quintessenz Zahntechnik/Germany

2021 - 4/2021 QDRP France

Competitions

2013 – 6th place at the 8th KunstZahnWerk contest by Candulor

2017 – 5th place at the 10th KunstZahnWerk contest by Candulor

2017 – 1st place at the 10th KunstZahnWerk contest by Candulor as "Best Documentation“

2020 – 1st place at the 4th Panthera Master Cup by Panthera Dental

Memberships

NGSC Noritake Greek Study Club

DGZI German Society of Dental Implantology

IASPE International Association for Surgical Prosthetics and Epithetics

Key Opinion Leader (KOL) at company MPF Brush Company

Key Opinion Leader (KOL) at company Candulor

Key Opinion Leader (KOL) at company Kuraray/Noritake

MDT ANDREAS CHATZIMPATZAKIS

Greece

Andreas graduated from the Dental Technology Institute (TEI) of Athens in 1999. During his studies he followed a program at the Helsinki Polytechnic Department of Dental Technique, where he trained on implant superstructures and all ceramic prosthetic restorations.

From the year 2000, he is running the ACH Dental Laboratory in Athens, Greece, specialized on refractory veneers, zirconia and long span implant prosthesis.

ACH Dental Laboratory is Co-operating lab with the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens for the MSc degree in Dental Laboratory Materials.

From 2016 he is key opinion leader for the MPF Brush.co.

On 2017 he visits Japan where he trained from Hitoshi Aoshima, Naoto Yuasa and Kazunabu Yamanda and becomes International Trainer for Kuraray – Noritake company.

In 2018 he became Editor-in-chief for the dental technician magazine “LABORAMA” published by OMNIPRESS co.

On 2019 he studies carving, morphology and all ceramic restorations at the Osaka Ceramic Training Center by Shigeo Kataoka.

On 2019 he establishes the Dental Technicians’ Coaching Services and coaches dental technicians to improve their work.

Andreas has also conducted several lectures and hands on seminars in Greece and abroad and published articles in Greek and international magazines.

His lecture “An exciting journey … to be a dental technician” is about inspiring dental technicians to improve their work by observing and emulate natural teeth using the internal live stain technique.

Article first published in Labline Magazine Issue 45, Spring 2022 edition.